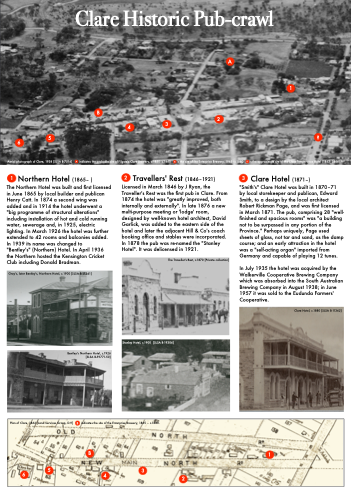

The Clare Historic Pub-crawl

| From the early 1870s to 1920, the township of Clare boasted six pubs, spread along the half kilometre of the Main North Road. This was the same density of hotels as along Rundle Street in Adelaide. Furthermore, in 1871 there was a pub for every 201 inhabitants of Clare, compared to an estimated 216 for Adelaide and 368 for South Australia as a whole. Yet all six pubs seem to have been well patronised especially by commercial travellers, squatters, carters and grape-pickers. On the other hand, there was little public drunkenness or lewd behaviour and, despite the usual over-zealousness of the local police and Inspector of Public Houses, Clare publicans were rarely charged with more than minor transgressions of the Licensing Acts. None seem to have received formal warnings from the relevant authority, the Licensing Bench, and none lost their license... until 1918 when, over just a few years, Clare lost three of its six pubs. Like other Liquid History self-guided historic pub-crawls, the Clare Historic Pub-crawl can be freely downloaded for non-commercial purposes by clicking on the image above. |  |

[Click on the image to download, approx. 9MB] |

...and a short note on the loss of three Clare pubs, 1910-21:

the Temperance Movement, Local Option polls and the East Midland Licensing Bench

Of the several ways in which pubs could lose their licenses in early twentieth century South Australia - poor management by the publican, insolvency of the owner, rationalisation by a brewery-owner, redevelopment of the property - the most spectacular was as a result of a 'Local Option Poll'. In simple terms, local option polls were a plebiscite whereby electors voted on issues related to the regulation of the sale of liquor such as, at different times, Sunday trading, 6 o'clock closing or the number of licensed premises in an local option or electoral district. Understandably local option polls were and still are linked inextricably to the public campaigns by the Total Abstinence and Temperance Movements of late nineteenth and early twentieth century South Australia [1]. However, the lost of the three licenses in Clare was, I propose, a little more complicated and only indirectly related to the Temperance Movement.

|

Total abstinence and temperance organisations - there was increasingly little difference between the two - were well represented in nineteenth century Clare. Organisations such as the Clare branch of the Total Abstinence Society (founded as early as 1859), the Clare delegation to the Temperance Alliance (by 1868) and Clare's Women's Christian Temperance Union (from about 1889?) campaigned actively for their cause, holding 'demonstrations' and public meetings, even opening a 'Temperance Hotel' (1862-1866) and, through the Stanley Local Option League (by 1908), by organising the petitions that initiated local option polls and mobilising voters.

The electoral District of Stanley which included Clare held no Local Option Polls until 2 April 1910 when 19 state electorates voted on not only parliamentary representatives but also whether the number of licensed premises in the District should be reduced by one third to four (the Temperance position), neither increased nor decreased (the Licensed Victuallers' Association and breweries' position) or left to the discretion of the regional Licensing Benches. |

|

|

In the electoral District of Stanley, 38.6% voted for reduction, 47.0% for no increase or decrease and 8.8% for the discretion of the Licensing Bench; although the numbers were closer for Clare itself (40.1%, 42,4% and 11.4% respectively), the majority voted for no change in the number of licenses [2]. Clare's six pubs appeared to be protected, at least until the next Local Option Poll.

Contrary to the outcome of the 1910 Local Option Poll in the District of Adelaide, in March 1917 the Midland Licensing Bench attempted to de-license a number of city hotels, leading to 'the Adelaide Hotel test case' that ascended through the courts from the Supreme Court of South Australia and in February 1918 to the High Court of Australia which upheld the power of the Licensing Courts to unilaterally reduce the number of licenses. In July 1919 this was referred to the Privy Council of Great Britain in July 1919 where the five Lords of Appeal of the Judicial Committee concluded that the Local Option Poll prohibited the Licensing Bench from increasing the number of licenses but that it could not legally forfeit its authority to decrease the number, given cause, in accordance with the full provisions of the Licensing Act of 1908. [3] Such 'causes' included the character of the licensee, the amount and quality of accommodation and related services and, significantly, whether a particular hotel was 'required by the public'.

On 1 March 1918, following the High Court's ruling "that the Bench had power to reduce the number of hotels if they so desired", the East Midland Licensing Bench granted special licenses for three months only to 21 public houses in the District, including all six in Clare; it also proposed to systematically review the hotels - a process identical to that by which Special Licensing Benches decided which particular pubs would lose their licenses as a result of a Local Option Poll. As the Blyth Agriculturist reported:

|

...Notice of opposition to [the re-licensing of] some of [the hotels] would be given, and a special meeting of the court would be held... The court ordered that the necessary inquiries be made, and that the inquiry with respect to the hotels of Clare be commenced at once. [Chief Inspector Davey and Inspector Watt gave evidence on the conduct, condition and lodgers' records for the six Clare hotels.] Chief Inspector Davey said that he considered at least two or three hotels in Clare could be closed, and quoted figures with respect to the population and number of hotels in other towns. The President of the Bench said the inquiry would be limited to Ford's, the Globe, and Commercials hotels, although the others might also be called upon to give evidence [4]. |

Even before the formal inquiry began, the Bench seems to have decided that they would not renew the licenses of two of the three named Clare hotels: Ford's, the Globe and/or the Commercial Hotels [5]. In such circumstances, the owner of the Globe, Julius Victorsen Jr, informed the Bench that "there was no intention of applying for a renewal of that license" [6]. From April 1918 until November 1919 the Bench continued to hear evidence on the Clare pubs, particularly the suitability of Ford's and the Commercial and it continued to grant special short-term licenses, pending the outcome of the Adelaide Hotel test case [7]. At its meeting on 12 November 1919, the Bench finally decided that

|

...No difficulties exist in respect to the continuation of the licences of Bentley's, the Stanley, and the Clare hotels. The decision as to which should be closed rested with Ford's and the Commercial hotels... The court was of the opinion that the claims of the Commercial hotel for continuation of licenses was superior from a structural point of view [counsel for the Commercial having submitted plans for the effective rebuilding and modernising of the hotel]. |

The voluntary withdrawal of the Globe and the de-licensing of Ford's should have satisfied the requirement of the Licensing Bench to reduce the number of licenses by two. However, despite assurances that there were plans to upgrade the hotel, on 9 February 1920 Inspector Davey reported that "the Stanley hotel at Clare is a very old house and most inconvenient, and in my opinion should be demolished and a modern building erected. I think the important town of Clare warrants another first-class residential hotel in addition to those already there" [10]. On 22 February 1921, the Bench eventually 'refused' the Stanley's license and the property, "highly suitable for a Coffee Palace", was offered for sale [11]. A subsequent attempt to renew the license was rejected by the Bench in August 1925 [12] and what was the oldest hotel in Clare was demolished in July 1927.

By the beginning of 1921, therefore, the three magistrates of the East Midland Licensing Bench, on the advice of the Chief Inspector of Licenses and two or three subordinates, achieved what the temperance movement and the Local Option Poll of 1910 could not in Clare and the District of Stanley. At best the influence of the various prohibitionist and temperance organisations was indirect and political rather than as a popular movement using local option polls to force pub closures. The closure of the Clare pubs was about accommodation and the other services offered by hotels, not about the consumption of alcohol.

In the Local Option Poll of March 1927, the last systematic prohibitionist campaign, the District of Stanley voted 66.5% for no change in the number of pubs compared to 29.5% for a decrease (to two); for Clare itself 73.4% voted for no change and 22.3% for reduction [14].

The Commercial Hotel (Taminga), 1921

|

Notes

| 1 | Although focussed on the pubs of Adelaide, Alison Painter's "Adelaide Hotels and Temperance 1860-1930" (downloadable or in Brian Dickey (ed), William Shakespeare's Adelaide 1860-1930, Adelaide, Association of Professional Historians, 1992, pp.87-105) provides as good an overview of the Temperance Movement and Local Option in South Australia as anything else currently available. |

| 2 | Northern Argus, 8 April 1910, p.3 |

| 3 | Express and Telegraph; 29 March 1917, p.2; Daily Herald; 20 June 1917, p.7; Express and Telegraph; 14 August 1917, p.1; Express and Telegraph; 1 March 1918, p.1; Register; 21 July 1919, p.4; |

| 4 | Blyth Agriculturist 8 March 1918 p.3 |

| 5 | According to the evidence of the Inspectors of Licensing, the Northern hotel had accommodated 4781 persons during the year; the Clare hotel, 3932; the Stanley hotel, 3230; Ford's hotel, 407 over three months or 1628; the Globe hotel, 1191; and the Commercial hotel, 2269. Both Inspectors considered that all the hotels were "well conducted and in good order". However, Chief Inspector Davey believed that "there were too many hotels in Clare... and some of them should be closed... [He] considered that two or three hotels in Clare could be closed and quoted figures with respect to the population and number of hotels in other towns." [Blyth Agriculturist 8 March 1918 p.3] |

| 6 | Northern Argus, 12 April 1918, p.5; Northern Argus, 6 December 1918, p.3 |

| 7 | Blyth Agriculturist 12 April 1918 p.2; Northern Argus, 14 March 1919, p.3; Northern Argus, 16 May 1919, p.5; Blyth Agriculturist 14 November 1919 p.2 |

| 8 | Blyth Agriculturist 14 November 1919 p.2 |

| 9 | Blyth Agriculturist, 4 March 1921, p.4 s |

| 10 | Northern Argus, 20 February 1920, p.3 |

| 11 | Blyth Agriculturist, 4 March 1921, p.4; Northern Argus, 13 May 1921, p.2 |

| 12 | Northern Argus, 21 August 1925, p.7; Northern Argus, xxx |

| 13 | Northern Argus, 20 November 1925, p.7 |

| 14 | Blyth Agriculturist, 1 April 1927, p.2 |

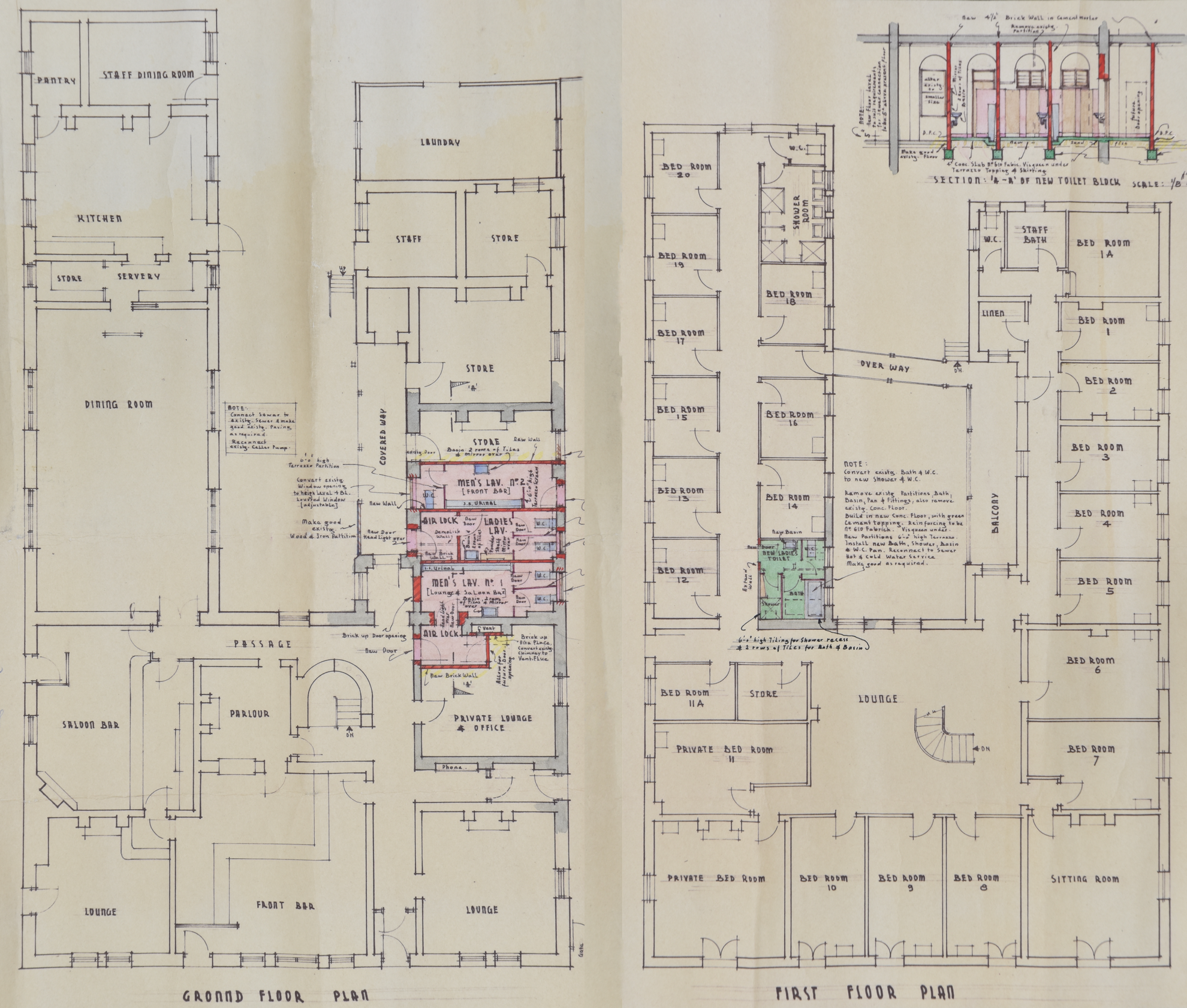

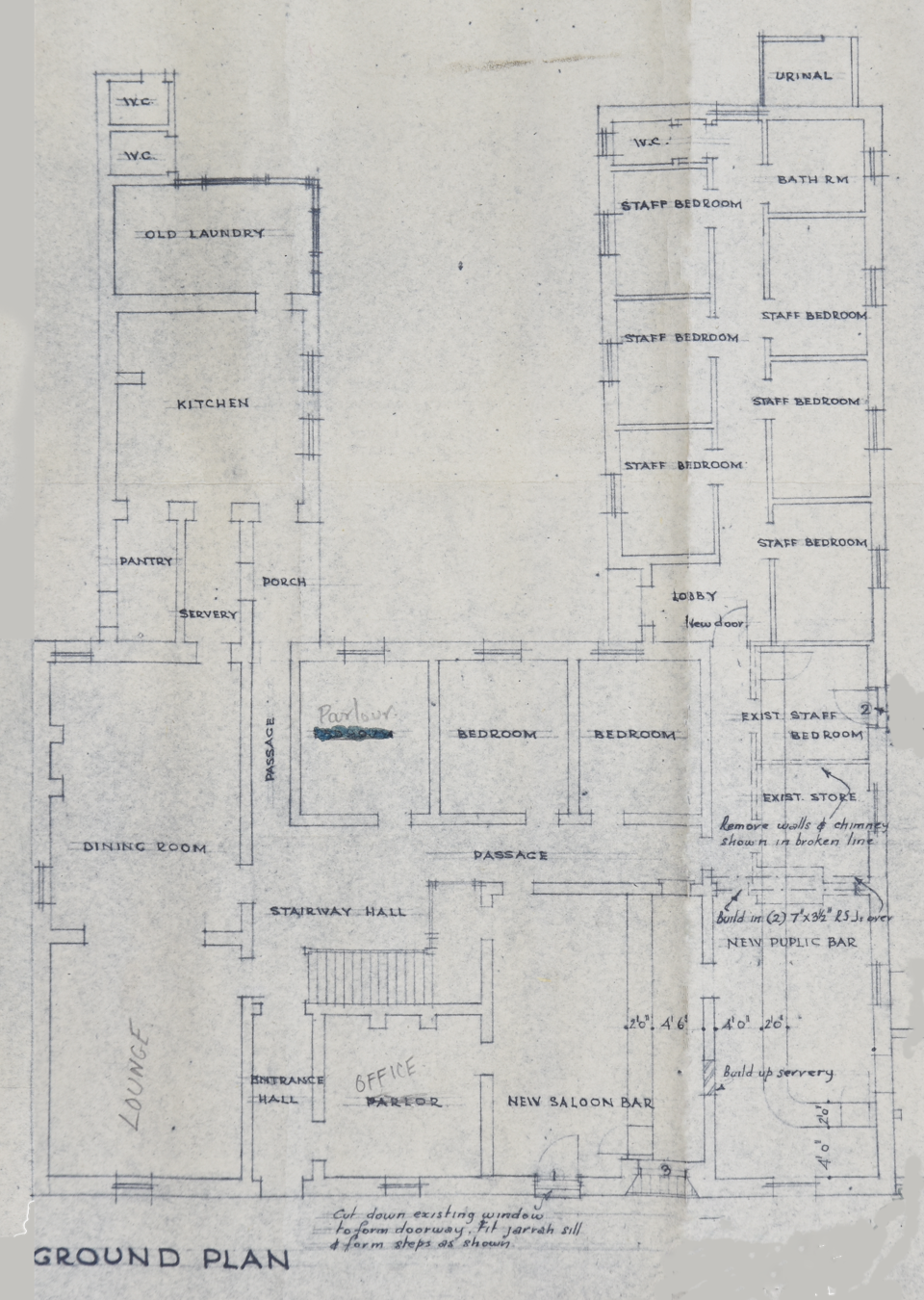

Architectural drawings of the Commercial Hotel 1956, and the Clare Hotel 1964

|

Below: Architectural plan of the ground and first floors, Clare Hotel, 1964. (Composite image and detail of originals)

[SRSA GRG67/34/00000/34] Right: Architectural drawing of the ground plan, Commercial Hotel, 1956. (Detail of original) [SRSA GRG67/34/00000/41]

Click image to enlarge in new tab |

|

Click image to enlarge in new tab |

Posted 10 April 2022 Original content © Craig Hill 2022