The "Spanish 'Flu" and closing South Australian pubs, 1918-1920

To curb the spread of the COVID-19 virus, on 22 March 2020 the Australian "National Cabinet" recommended restrictions on non-essential public gatherings including the closure of pubs, until further notice, across Australia. In South Australia the restrictions were implemented under the state's Emergency Management Act the following day. This is, I believe, the first time that any South Australian government has so broadly proscribed pubs for any reason and invites comparison with what happened during previous national health emergencies, particularly the so-called "Spanish 'Flu" of 1918-20.

The "Spanish 'Flu" was not the first nor is it the only lethal influenza-related pandemic. It is, however, generally regarded as the worst by any measure. This was the "mother of all pandemics", exceptional in both breadth and depth: it affected all corners of the globe, infecting about one third of the world's population and killing between 20 and 100 million. This represented a mortality rate among the infected of between 1% and 2.5% compared to 0.1% for recent influenza pandemics [1].

The first case of "Spanish 'Flu" in Australia was identified in early October 1918. The first notification of the disease in South Australia was on 18 January 1919. By the time the influenza had run its course, by early-mid 1920, an estimated 11,552 deaths had been reported nationally (a per-capita mortality rate of 2.12%) and 540 deaths in South Australia (1.18%) [2].

Australia, and South Australia in particular, therefore fared much better than the rest of the world. Then as now, South Australia's relatively low infection and mortality rates were probably as much the benefit of the state's isolation, its few points of entry and its low population as much as the official public health measures or advances in medical science. As the British science journalist, Laura Spinney, has pointed out recently, that without a vaccine, "what do we have? We have strategies of containment, strategies that are collectively known as social distancing. And those are surprisingly unchanged since 1918, or even since much, much before that." [3] The South Australian government effectively assumed responsibility for public health, including the control of epidemics, with the Public Health Act of 1873. Since then, through at least seven major influenza pandemics [4], official responses have comprised more or less the same basic elements: quarantine (this and related powers were eventually assumed by the Commonwealth in 1908) and closing of state borders, isolation, mandatory notification, inoculation against complementary diseases such as pneumonia, public health programs that emphasised personal hygiene and protection (ie masks) and, above all, what we now call "social distancing". For the worst of the pandemics, "social distancing" has been enforced by the closure of places in which people habitually congregate, including, in some States of Australia, pubs.

The "Quarantine Camp" on the Jubilee Oval, Adelaide, March 1919

The "camp" was established in March 1919 to quarantine arrivals by train, mostly from Melbourne, less so from Perth; (maritime arrivals were quarantined temporarily on the ships, or on Torrens Island); the tents housed men, women were accommodated in sheds on the same site. Jubilee Oval was part of the Royal Agricultural and Horticultural Society of South Australia's show grounds, now the north-eastern corner of the University of Adelaide. The photograph was taken looking north from approximately behind Elder Hall; Frome Road is on the right, the River Torrens on the left. The nearest pub was about half a kilometre away. [SLSA PRG 280/1/9/374]

Closing the pubs

In 1919 the authority in matters of public health was vested in the state parliaments, excepting only the Commonwealth's quarantine and immigration powers. As Humphrey McQueen has shown [5], after the failure in November 1918 to coordinate across the Commonwealth measures to restrict the spread of the disease, the states more or less went their own ways, including in the regulation of "social distancing" and including whether or not they closed pubs.

On 3 February 1919 New South Wales proclaimed that "all premises licensed for the sale of liquor within the county of Cumberland [effectively all metropolitan Sydney] shall be closed and kept closed for the sale or consumption of liquor until a further order shall be made." Victoria followed on 11 February, closing all hotels and registered clubs within a radius of 15 miles (24 kilometres) of the Elizabeth Street Post Office. On 11 August, Tasmania also closed its public houses and restricted the number of resident patrons who could be in a hotel bar to two and the time they could remain there to five minutes. Western Australia did not close pubs unless they were the source of a serious outbreak as happened to two 'hotels' in the notorious Hannan Street, Kalgoorlie, in early July 1919; the Moora Hotel in Bunbury was also closed on 15 August 1919 but to establish a temporary quarantine station. Queensland does not seem to have closed its licensed presmises.

The South Australian government and its public health authorities also seemed confident that closing the state's borders and then quarantine (of the 'suspected') and isolation (of the infected) were sufficient to contain the disease and that the more extreme measures enacted in New South Wales and Victoria were unnecessary. Moreover, as far as I have been able to determined, there appears to have been no serious discussion in Parliament and little in the press about the effectiveness of these or alternative measures such as regulation of "social distance" in general or closing the pubs in particular. In South Australia in 1918-1920, pubs were not, it seems, regarded as a hazard to public health.

Despite the ravages of the "Spanish 'Flu", the South Australian government did not close the pubs, at least not for medical reasons.

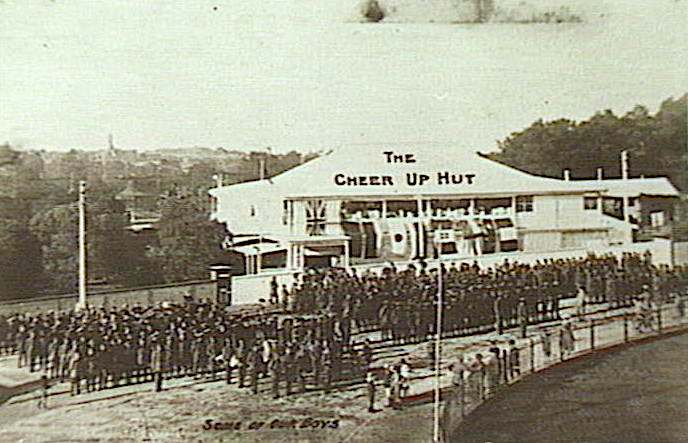

Returning soldiers at Outer Harbour, 1919 [SLSA PRG PRG-280-1-22-114]

The real threat to public health was the repatriation of Australian soldiers from Britain and Europe, coincidentally at about the same time as the outbreak of the 'Spanish Influenza'. Understandably, the authorities were reluctant to link the introduction and transmission of the disease to the home-coming of Australia's national heroes. However, from October 1918, when the outbreak was declared an epidemic, the Commonwealth Director of Quarantine, Dr J H L Gumpston [6] automatically quarantined all ships entering Australian ports, including returning hospital and troop ships, generally for between 4 and 7 days.

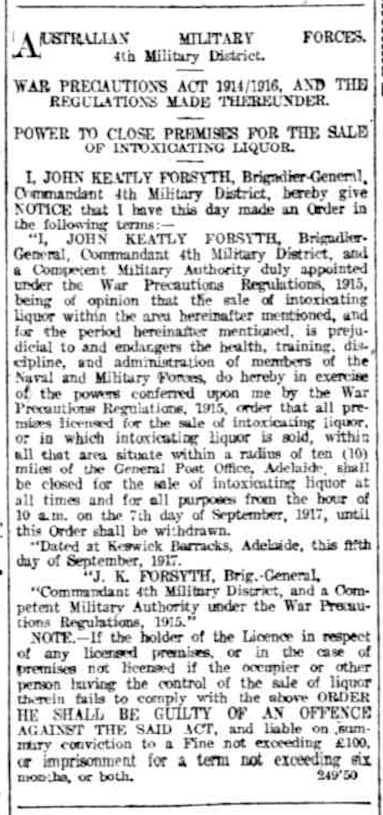

The War Precautions Regulations and South Australian pubs