After a number of recent false-starts, the old Stag Inn has been refurbished and reopens today,

10 August 2018, 169 years to the day that The Stag was first licensed. Although not the oldest pub in Adelaide, nor the biggest, nor the grandest, nor whatever the superlative, since the mid-nineteenth century The Stag has been an Adelaide landmark, an icon for the East End. Its built heritage value has been recognised by both the South Australian State Government and The National Trust. The following, hopefully the first in a series on The Stag, is an attempt to put some history inside the building, to encourage people to visit and enjoy The Stag and maybe even adopt it as their local.

The Stag Inn - the beginning

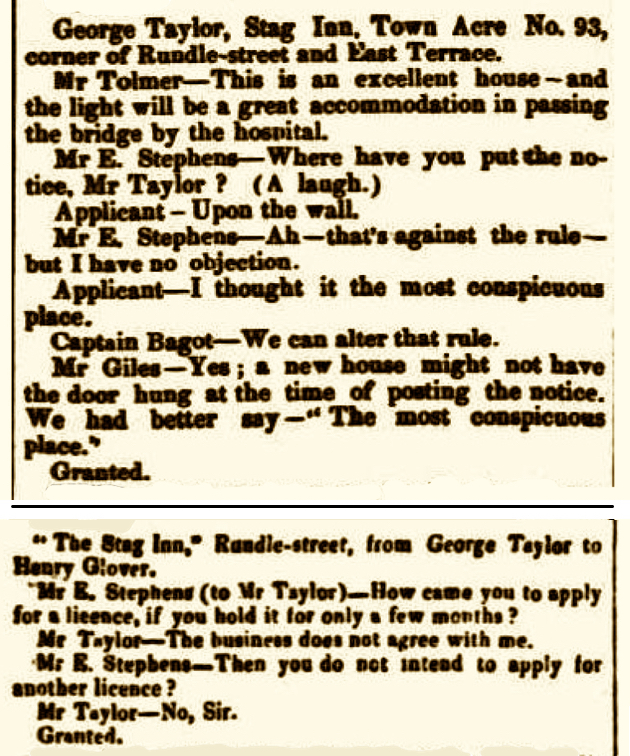

The Stag Inn was first licensed on 10 August 1849. Or more accurately, on that date the Bench of Magistrates responsible for approving all manner of licenses, granted Mr George Taylor a publican's general licence to conduct a public house known as [The] Stag Inn on "Town Acre 93, corner of Rundle-street and East Terrace"; the licence did not become effective until 18 September when it was officially gazetted. A licensed public house named "The Stag Inn" or "The Stag Hotel" or, now, "Stag Public House", or more commonly know as just "The Stag" has remained on the same site since, for 169 years.

Incidentally, The Stag was probably not completed at the time that the license was granted. The licensing magistrates mused that Taylor had posted the notice of application on a wall rather than on the main door, as required under the regulations, because the door hadn't yet been hung.

Proceedings of the [Licensing] Bench of Magistrates: top: initial licensing of The Stag Inn, 10 August 1849, below: transfer of license, 10 December 1849. (The South Australian, 14 September 1849 and 12 December 1849)

Taylor purchased two adjoining lots with frontages on Rundle Street on Town Acre 93 from the South Australian Company in June 1848. The [Adelaide] City Commission Assessment Book for 1850 lists George Taylor as the owner of a "2 story Brick and Stone Licensed House with Stables called the 'Stag Inn'" with rateable value of ₤90. The second property, to the west of The Stag Inn on Rundle Street was described as a "2 story Dwelling, Brick shop and Outbuilding", a significant building rated at ₤27. This 'shop' to the west of The Stag Inn or more likely a building that replaced it possibly in about 1880, was almost certainly incorporated into the The Stag when the pub was rebuilt in its more or less present form in 1903 [see photographs below].

Above: The Stag Inn, looking west down Rundle Street, in about 1866. The photograph shows the earliest features of the pub - its simple structure, the champfered corner with main door, the absence of verandhas - as well as the lean-to (stables) at the back, what looks like a rough privy, advertising posters, the horse trough and the Sugar Gums sheltering the north-facing side. The lamp over the door was required by the licensing regulations. Note also the lack of people on the street, although it's possible that the photograph was taken at lunchtime and in mid-summer.

Below: The Stag in 1903, not long before demolition. The additions to the original structure probably in the 1880s are highlighted, including (in red) the building that replaced Taylor's original 'brick shop'. The late nineteenth century changes also incorporated "Stag Lane", a private lane providing access to the rear of The Stag (←).

The derivation of the name "Stag Inn" is not known; contemporary sources give no clue. Typically early Adelaide pubs were named after localities, occupations, ships or familiar public houses in Britain and it is likely that this latter was the case with The Stag; as they say, more research is needed.

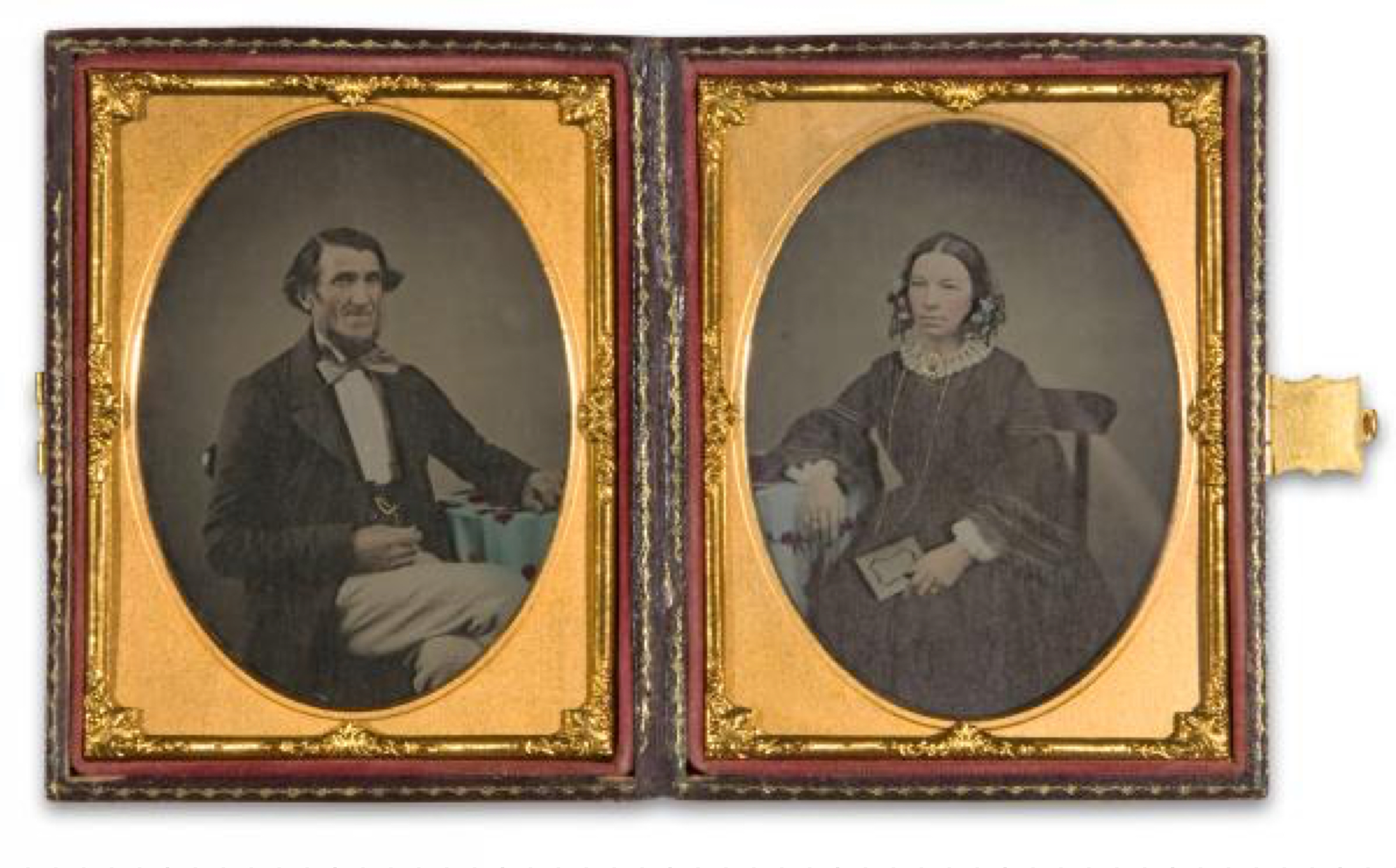

Part of this problem is identifying the correct George Taylor, his origins and early colonial life and here too we need more research. From his wife Anne's, obituary, we do know that the relevant George Taylor was a "former builder of Grenfell Street"; they were married in 1843 and "after a success career they returned to England where Mr Taylor died in 1874" (The Adelaide Observer, 8 March 1884). Anne Collis Taylor (nee Pratt) arrived in the colony on the D'Auvergne in March 1839; other passengers on the ship included the family of Robert Taylor including his son George and it is possible but highly speculative that Anne married this George. It might not be completely coincidental, however, that Anne's sister was married first to Walter Waite and later to Charles Brooks, both of whom were later owners and licensees of The Stag, hinting that the interest in public houses might have come more from Anne's family than George's. It seems that George and Anne had no surviving children.

George and Ann Taylor, c1856 (Art Gallery of South Australia)

George and Ann Taylor, c1856 (Art Gallery of South Australia)

George Taylor would now be described more as a "developer" than a builder - as was common for builders in colonial South Australia: purchasing land, building on it and then leasing or selling the buildings, reinvesting the profit. He was also described as a "general storekeeper", as a carter and even as a blacksmith. But Taylor was primarily a developer who specialised in the building of pubs. According to his nephew, William Nicholas Waite, Taylor also built the 'Grapes' [in Grenfell Street to the west of the current Producers, stopped trading in 1881] and The Exeter (The Advertiser, 10 January 1903) and it's possible he also rebuilt the Golden Pheasant in Noarlunga (stopped trading in the 1870s). To benefit as quickly as possible from his investment, Taylor transferred the lease (but not ownership) of The Stag to Henry Glover almost as soon as The Stag was completed, on 10 December 1849, because, he claimed, "the business did not suit him" (The South Australian, 11 December 1849).

Taylor seems to have been very successful in the businesses that did suit him and he and his family were more than modestly well-off. In December 1850 Taylor was admitted to the Grand Jury List based on real estate valued at over ₤500, then not an inconsiderable sum (South Australian Gazette and Mining Journal, 14 December 1850). When Taylor's estate was finally settled in April 1902, it comprised The Exeter Hotel, two 5-roomed cottages, The Stag Inn, two shops adjoining The Stag Inn (occupied by William Charlick), three other shops and two dwellings, all in the vicinity of The Stag and The Exeter, as well as two 4-roomed cottages in North Adelaide and two 6-roomed houses in Norwood (The Advertiser, 5 April 1902).

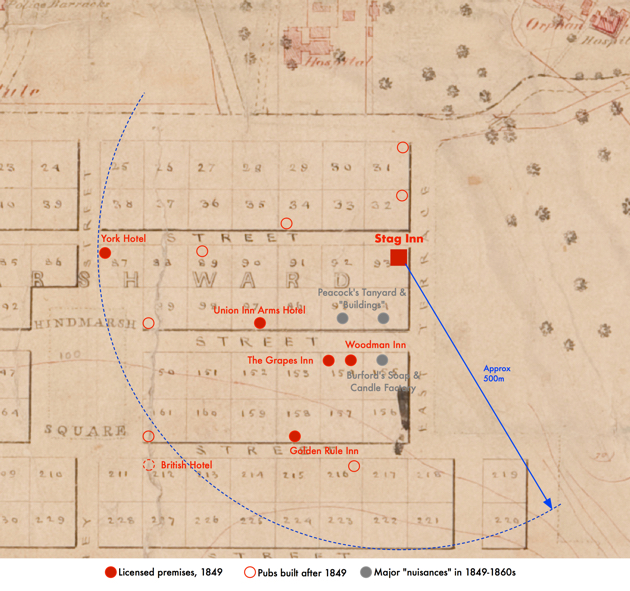

When Taylor purchased the land on which The Stag was built, development and economic activity in Adelaide centred on the West End (especially Hindley and Currie Streets), not the East End. With its proximity to the only reliable crossings of the River Torrens and the tracks leading to Port Adelaide and to the Emigration Camp in the West Park Lands, the north-western quarter of the city was the most populous, the most economically and socially active and therefore the most attractive for public houses offering local and itinerant customers accommodation, stabling, food and drink and other entertainments (see especially Patricia Sumerling). By comparison the East End stagnated. According to the assessment records for 1848, 28% of the 212 allotments within a 500 metre radius of The Stag (arbitrarily its 'catchment') remained unoccupied; and 25% of the land in this area was still owned by the South Australian Company, a situation that did not encourage investment. In 1903 an 'old colonist' described the The Stag site in 1849: "when [The Stag Inn] was built that portion of the city was regarded as almost beyond the bounds of civilization. There were only two or three other buildings in the neighbourhood, and no properly constructed roads on the eastern side of the hotel. East terrace had not been laid out, and the park lands between the Stag Inn and Kent Town were merely virgin scrub, intersected in various directions by rough tracks formed by bullock teams." (The Adelaide Observer, 24 January 1903)

What's more, in 1848-49, five other licensed public houses shared more or less The Stag's 'catchment':

- The Woodman Inn, now The Producers or To Let, first licensed in 1839;

- The Grapes Inn, licensed from 1840 to 1881 and since demolished;

- The Union Inn Arms, now on the site of The Crown and Anchor, licensed from 1847 to 1851;

- The Northumberland Arms which became the The Golden Rule Inn in 1849, licensed from 1847 to 1908 and subsequently demolished; and

- The York Hotel was licensed at about the same time as The Stag, in December 1849, and was rebuilt as the The Grand Central Hotel in 1910.

The Stag's closest licensed neighbours in 1849: the corner of East Terrace and Grenfell Street, c1865, showing The Woodman Inn (A) and The Grape Inn (B); Peacock's tannery is on the right of the photograph, Burford's soap and candle manufactory on the left.

From 1850 to the mid 1880s, the high point of the number of pubs in Adelaide, another seven licensed public houses were built within 500 metres of The Stag: The Swiss Hotel, now The Tivoli, in 1850; The Exeter in 1851; The Park Tavern, now The Griffins Head, in 1856; The Black Eagle, which became The Aurora, in 1859; The East End Market Hotel in 1868; Cohen's Family Hotel, now The Austral, in 1880; and The Botanic Hotel, built in 1876-77 and licensed from 1883.

Location of The Stag showing existing and future public houses, the nearby 'nuisances', the East Park Lands and carriageways in 1849.

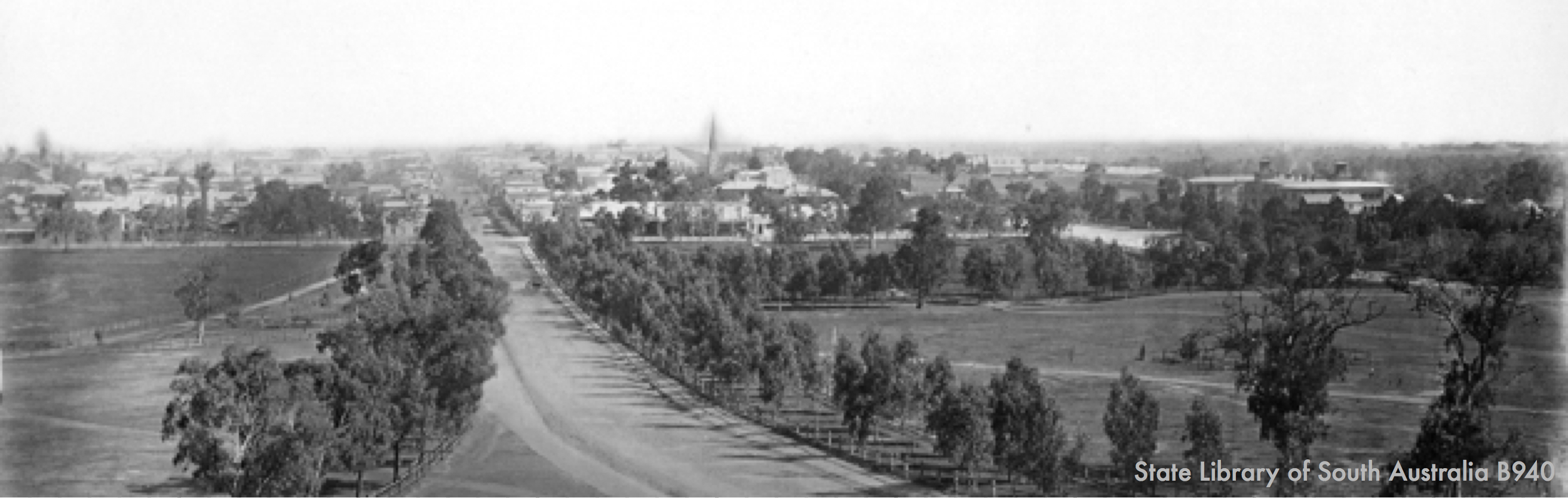

Two other factors also mitigated against the short-term success of The Stag - and the other East End pubs for that matter - from 1849 until at least the mid-1850s. Firstly The Stag was poorly connected to its natural constituency, the small farmers and tradesmen in the growing villages to the east and the north of the town. Until the mid-1850s the four main bridges over the River Torrens and even more importantly, the lesser bridges over the creeks running into the Torrens were poorly constructed, susceptible to flood damage and notoriously unreliable.

More critically for the East End, our founding fathers neglected to plan and build roads through the Park Lands especially directly east of Adelaide, crossing Botanic Creek which then ran through the East Park Lands. What is now Rundle Road, connecting Rundle Street to Hackney Road, seems to have been little more than a dirt track or more accurately a series of tracks converging on the Stag corner. As early as 1844 Taylor subscribed to a private fund for the repair of Adelaide's roads (Southern Australian, 28 June 1844). In 1851 Taylor and other East End rate-payers actively lobbied the City Commissioners "on the subject of the proposed continuation of the line of Rundle-Street to Bailey's nursery ground [in Hackney]" (South Australian, 17 June 1851). Their resolutions fell on deaf municipal ears. Probably as much from commercial self-interest as civic duty, therefore, in 1854-55 a group of Rundle Street landowners, including Taylor, raised another public subscription to build a small bridge over Botanic Creek and thereby attempting to force the Council to survey and maintain a good road over the Park Lands.

By 1857, however, as The South Australian Register (8 July 1857) editorialised:

|

"The Park Lands will never be other than a quagmire in winter, and a desert of blinding, suffocating dust in summer, unless properly-fenced roads are constructed through them... [The road leading from the Stag Inn to Kent Town] is one of the very worst in the Park Lands; because it connects Adelaide with the most thriving suburban townships; and because it is the road which, by its present dilapidated condition, most seriously compromises the efforts of the Norwood and Kensington Corporation to establish a good line of communication with Adelaide. The embankment leading down from the Stag Inn, and the wretched apology for a bridge which now crosses the creek, are altogether inadequate to the traffic of the locality, and will in all probability, if allowed to remain in their present state, eventuate in some serious accident... With such roads as now disgrace the Park Lands there is no alternative for vehicles but to deviate in all directions from the track...rendering it utterly useless." |

Not until June 1867 did the Adelaide Corporation finally tender for the forming and making of Rundle Road and it was finally useable from early 1868. Botanic Road, connecting North Terrace to Hackney Road, fared a little better but was still not completed until October 1860; ironically the formal opening was celebrated with a "sumptuous banquet" at The Stag, "prepared by the landlord, Mr W Waite…in the first style of the art. The company did ample justice to the delicacies which were spread in tempting profusion before them and the various wines were declared unanimously to be of excellent quality."

Rundle Road from Kent Town looking west across the East Park Lands, c1872; the Stag, still without the additions on the East Terrace frontage, is visible on the southern corner of East Terrace and Rundle Street.

Secondly, for much of the nineteenth century, the East End was hardly the most salubrious part of town. Even before Taylor built The Stag, in January 1849, several East End residents took William Peacock to court for creating a "nuisance, to wit, a hog sty and tanyard [tannery] on his premises in Grenfell Street" that caused offensive smells "not easy to describe" (Adelaide Observer, 27 January 1849). Throughout the 1850s the municipal authorities continued to receive complaints about the poor drainage, raw sewerage and the stench from both Peacock's tannery and also Burford's boiling down and soap manufactory, both at the east end of Grenfell Street, the stagnant water in Botanic Creek rendering it "unfit for domestic purposes and watering horses", the keeping of pigs, the noise from the Waterworks and so on, conditions that "inevitably tend to depreciate the value of the property in their neighbourhood and are most offensive to the inhabitants for a considerable distance around" (The South Australian Register, 8 March 1854). In August 1856 The Adelaide Observer summarised the "nuisance" of the East Park Lands:

|

"From the east end of Rundle-street to the creek, the Park Lands have been the licensed rubbish-yard of the city. Hundreds of cart loads of every description of refuse have, for a long time past, been ruthlessly scattered about upon the surface. Vegetable matter lies at leisure to decay; broken glass and bottles, mingled with old mattresses and tin-kettles; rags, bones, and dead dogs vary the scene with heaps of chemical refuse; alkalies decomposing, and mingling their scents with so many others, that the seventy distinct odours of Cologne might be fairly counted over again in Adelaide. We have no Torrens through the East Park Lands, but there is a small creek running all the summer, which is now the receptacle for every kind of filth..." (The Adelaide Observer, 16 August 1856). |

Another of Peacock's enterprises represented a more direct sanitary - and eventually moral - threat to the The Stag and its customers. "Peacock's Buildings", over 20 crude brick or pise 2-roomed cottages, most rented to the tannery workers, were singled out as amongst the most impoverished and unhealthy tenements in Adelaide. In February 1849 these were described as

|

"...a row of eight habitations, I cannot call them houses, divided into 16 tenements, the upper of which are accessible only by means of open stairs, or rather stepladders, in the rear. Their

dimensions are only 10 feet by 12 feet [3 x 4 metres] each. These have 100 persons occupying them, all of whom are compelled to use the same convenience, which adjoins one of the ladders, and

stands within two feet of the house. Many have died in them of fever, and others are dangerously ill of it. On the west side of the same buildings there are 12 houses belonging to the same landlord

[Peacock], all thickly inhabited and' having but one privy among them."

|

One of "Peacock's Buildings" (in 1890?)

The Stag was built in hardly the ideal location for a new public house. Nevertheless it not only survived but thrived, to become "the catch-house of the eastern suburbs".

|

"In the old coaching days.., the Stag was no small factor in the life of Adelaide and even of South Australia. There are folks who say they remember when it was 'the' house. As an old colonist remarked, 'in those days it was a mansion'. It's weighbridge, stables, and stockyard were extensively used, and the market gardeners of the forties were in the habit of dropping in for a glass when they brought their produce to market. Travellers, too, found the hostelry to their liking, and the compositors of those days considered it handy after an all-night sitting (or standing), so that the landlords 'made a very good thing of it'. (The Advertiser, 10 January 1903) |

But how The Stag became the preeminent public house in the East End is, as they also say, another story.

Posted: 10 August 2018. Original content © Craig Hill 2018.