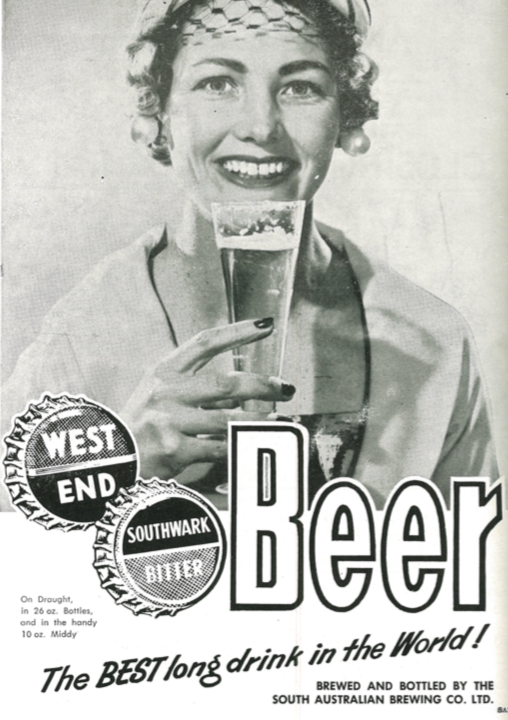

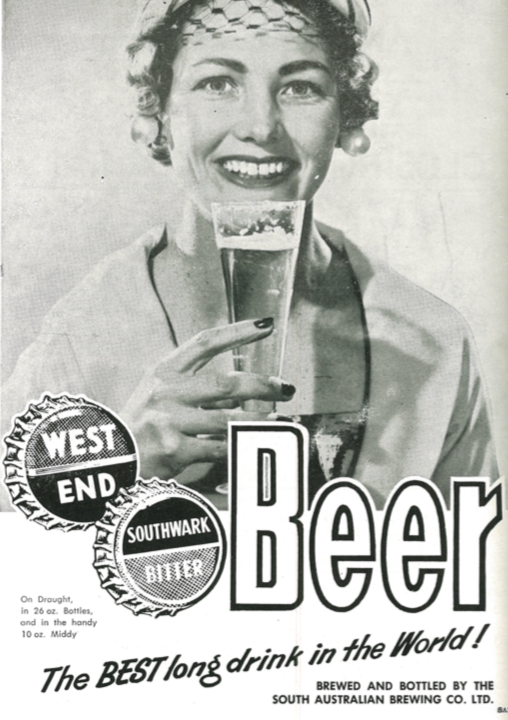

Advertising directed at women drinkers, 1960

[ULVA Hotel Gazette, March 1960]

|

|

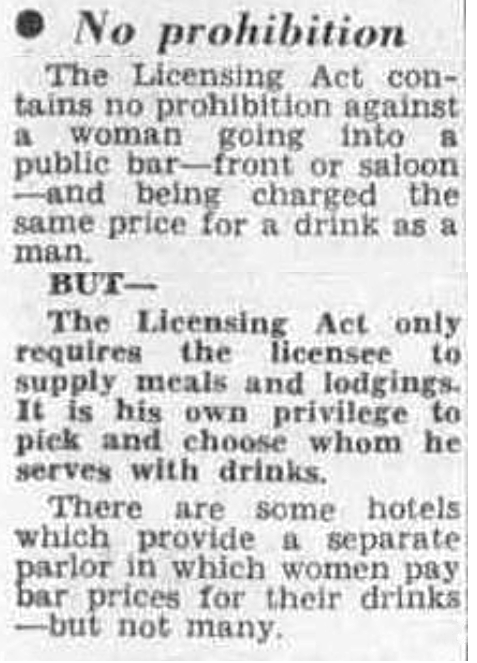

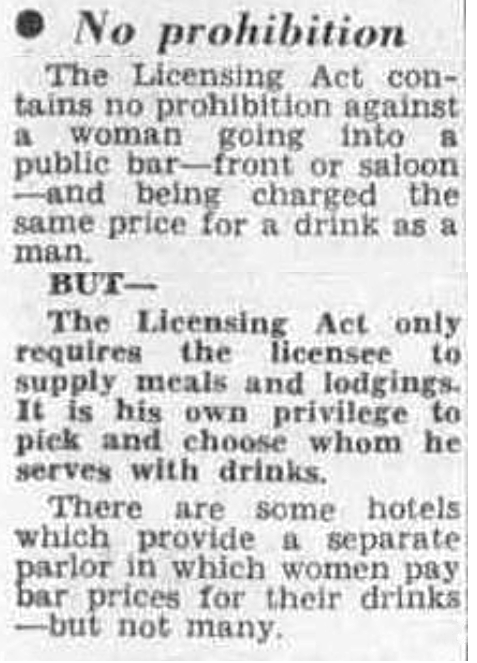

No prohibition on women in pubs

[The News, 1 September 1954, p.3]

See also "He took a girl into a bar...", The News, 30 July 1952, p.2, attached.

|

|

In South Australia, women have not been legally precluded from drinking in licensed premises. Since 1863 governments have restricted to whom publicans could serve liquor based on age or race or sobriety but, with several exceptions [see below], these prohibitions applied equally to men as to women. Some legislation facilitated if not encouraged women to go into pubs; for example, the Licensing Act of 1880 required for the first time that public houses have "decent and separate places of convenience for both males and females and urinals on or near to the premises for the use of customers... so as to prevent nuisances and offenses against decency". Similarly, although the minimum age at which liquor could be purchased has been legislated periodically since 1863, at no time have children been barred from pubs. Arguably, South Australian pubs have always been women- and family- tolerant if not -friendly.

On the other hand, publicans were not legally required to sell or supply liquor to anyone, male or female. Until the South Australian Sex Discrimination Act of 1975, whether a publican served or refused to serve women was entirely at their discretion. If there was a 'ban' on women drinking in pubs in general, it was informal and 'cultural'.

|

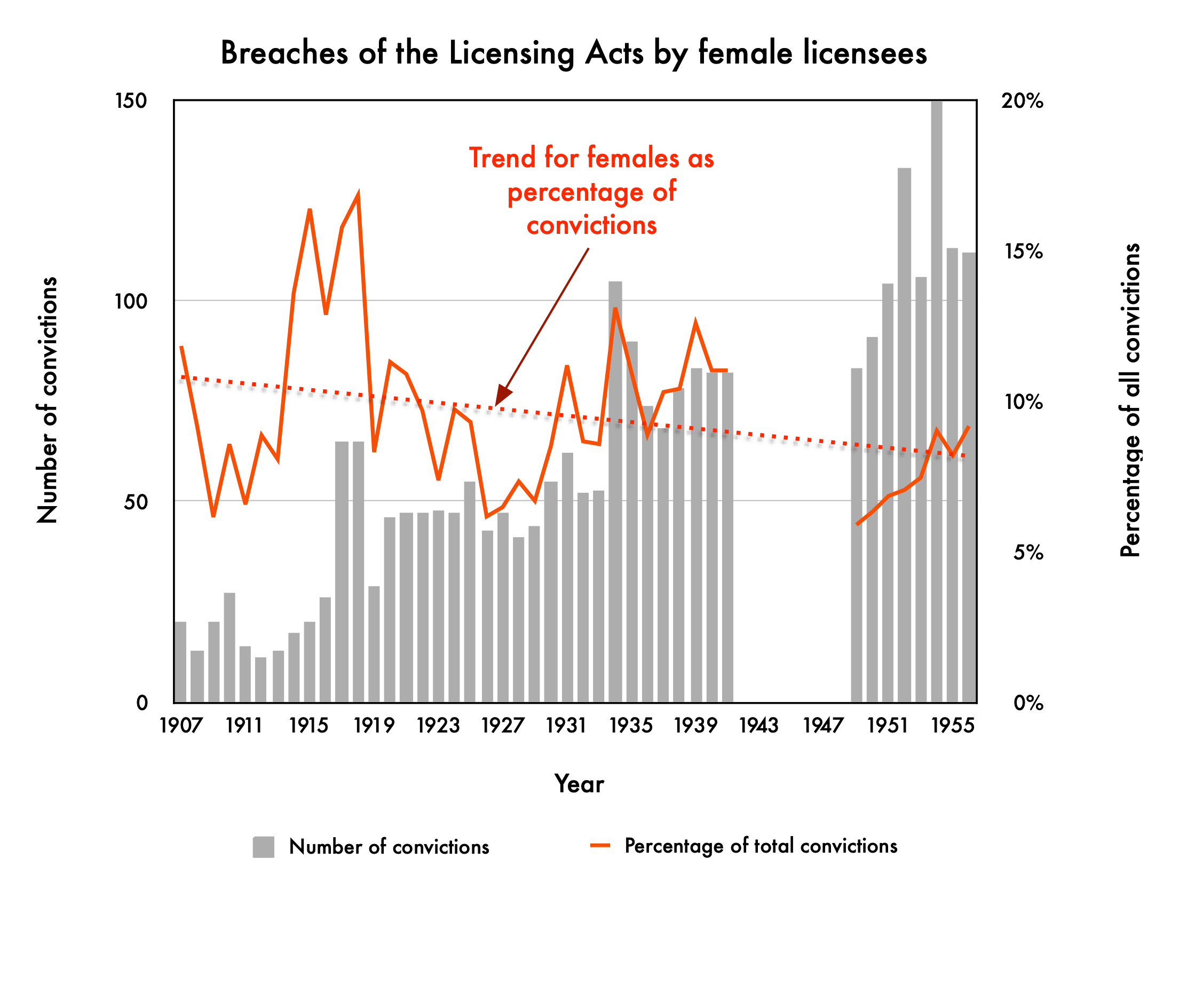

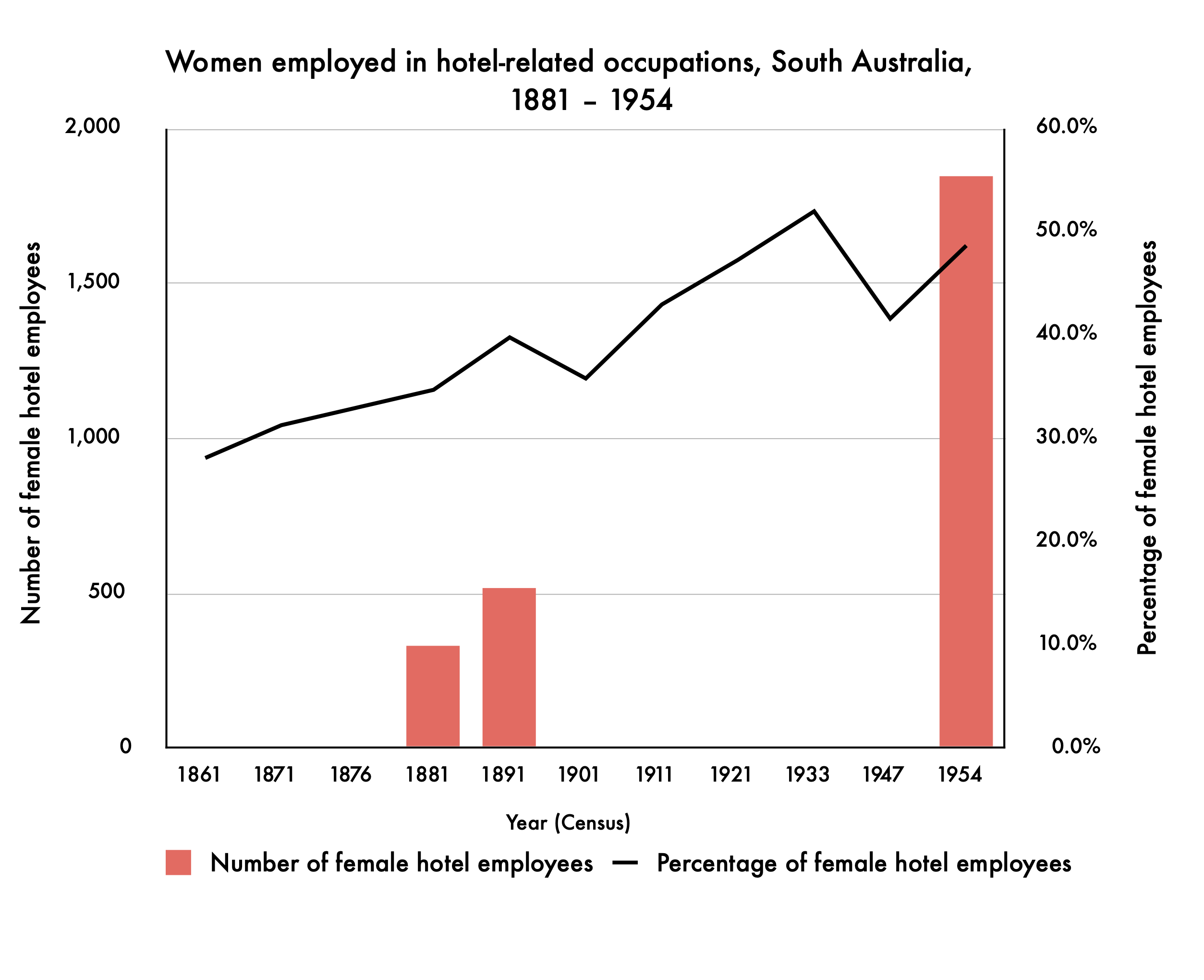

Nevertheless, from the early twentieth century, various governments imposed limitations on the rights of women as licensees, as barmaids and as patrons in South Australian pubs. The table linked below summarises the major South Australian legislation which applied to the roles of women in licensed premises from 1837 to 1967. The information was sourced from the

Australasian Legal Information Institute databases, mostly historic South Australian Acts and Amendments. This project is a work in progress and the table will be updated as necessary.

A summary of the major South Australian legislation related to women in public houses v1 April 2023 is freely downloadabe for private, non-commercial research.

The list does not include laws on women's property rights (applicable to women as pub owners), on women's right to vote (and therefore their influence on local option polls, the occasional plebiscites which determined the number of pubs in a given area) or on industrial matters (related to working conditions and wages of hotel staff, including barmaids) and similar legislation that would be necessary for a comprehensive history of women in pubs in South Australia.

|