|

|

South Australia's Working Men's Clubs

Last June Pete Brown, acclaimed British author on pubs and beer and "Industry Legend", published Clubland: How the Working Men's Club Shaped Britain, a "journey through the intoxicating history of the working men's clubs...from the movement's founding by teetotaller social reformer the Reverend Henry Solly [in the 1860s] to the booze-soaked heyday [a century later]." Given that much of colonial South Australian pub and drinking culture - from licensing legislation to preferred beer styles - was heavily influenced by what was happening in Britain, for us Clubland... poses questions of whether there was a similar movement here and, if so, what happened to it and any local Working Mens' Clubs. Although benevolent and recreational clubs existed at the time, it seems that the publication and wide distribution of Henry Solly's Working men's social clubs and educational institutes in 1861 and the foundation of the Working Men's Club & Institute Union (CIU) the following year were the catalysts for the development of Working Mens' Clubs in Britain and elsewhere, including South Australia [1].

Working Mens' Clubs (WMCs), established according to Solly's model, were a mixture of working class moral and intellectual improvement through 'rational recreation', upper- and middle-class philanthropy and workers' self-determination. As Pete Brown wrote

|

|

While continually stressing that working men should be free to organise and run their own clubs, Solly had some definite and detailed views on exactly what those men should be choosing to organise and run. "Suitable premises," he wrote, should contain: "...rooms to be used for conversation, refreshments, recreation etc., and others for classes, reading, lectures and music. A library of entertaining and instructive books, scientific apparatus, diagrams etc., a supply of newspapers, and some works of art should be aimed at. The services of efficient teachers, paid and unpaid, should be procured; Discussion Classes, to awaken thought and a desire for knowledge, should be established; readings from amusing and eloquent writers, interspersed with music and recitations, should be given periodically" [2].

|

This was industrial-scale working class advancement based on self-improvement, education and temperance. At least initially, Solly's rules for WMCs prohibited the consumption of liquor and gambling on club premises. This was later changed to a strong recommendation. Nevertheless, with such WMCs, there was always a sense of someone looking over the workers' shoulders, either the patrons or the licensing regulators. As places for workers' relaxation and conviviality the early WMCs were therefore antithetical to egalitarian public houses.

As early as July 1856 the Australian press reported on Birmingham's "Public Recreation Society", a pre-cursor to the WMCs, and, from mid-1863, on the growth of the British WMCs, the progress of Solly's CUI and the founding of Australian clubs. The first WMC in Australia was established in Hobart in October 1864 [3], providing a concrete example for other's to imitate. In Adelaide in December 1863, for example. a writer for the Adelaide Express described the spread of WMCs throughout Britain and questioned whether "some movement of the kind might not be initiated with advantage in Adelaide"; and, at the inaugural meeting of the South Australian Total Abstinence Society on 19 January 1864 the working men of Adelaide were urged to establish WMCs as liquor-free alternatives to public houses [4].

The "Glenelg Working Mens' Club" was the first South Australian WMC reported in the press, in mid-1865; it was, however, only nominally a WMC, attracted few workers and seems to have dissolved within just two months [5]. The modest number of Solly-esque WMCs which followed were equally unsuccessful. As far as I can determine, the ten or so WMCs founded from 1865 to the mid 1890s were also WMCs in little more than name, they failed to enrol enough working class members to become self-sufficient and their management remained mostly in the hands of their upper- or middle-class patrons. Judging by newspaper reports within a year of their foundation, most of these clubs had been transformed into social clubs, were absorbed into Mechanics' Institues, amalgamated with other organisations such as sporting clubs; several became insolvent; most simply closed [6].

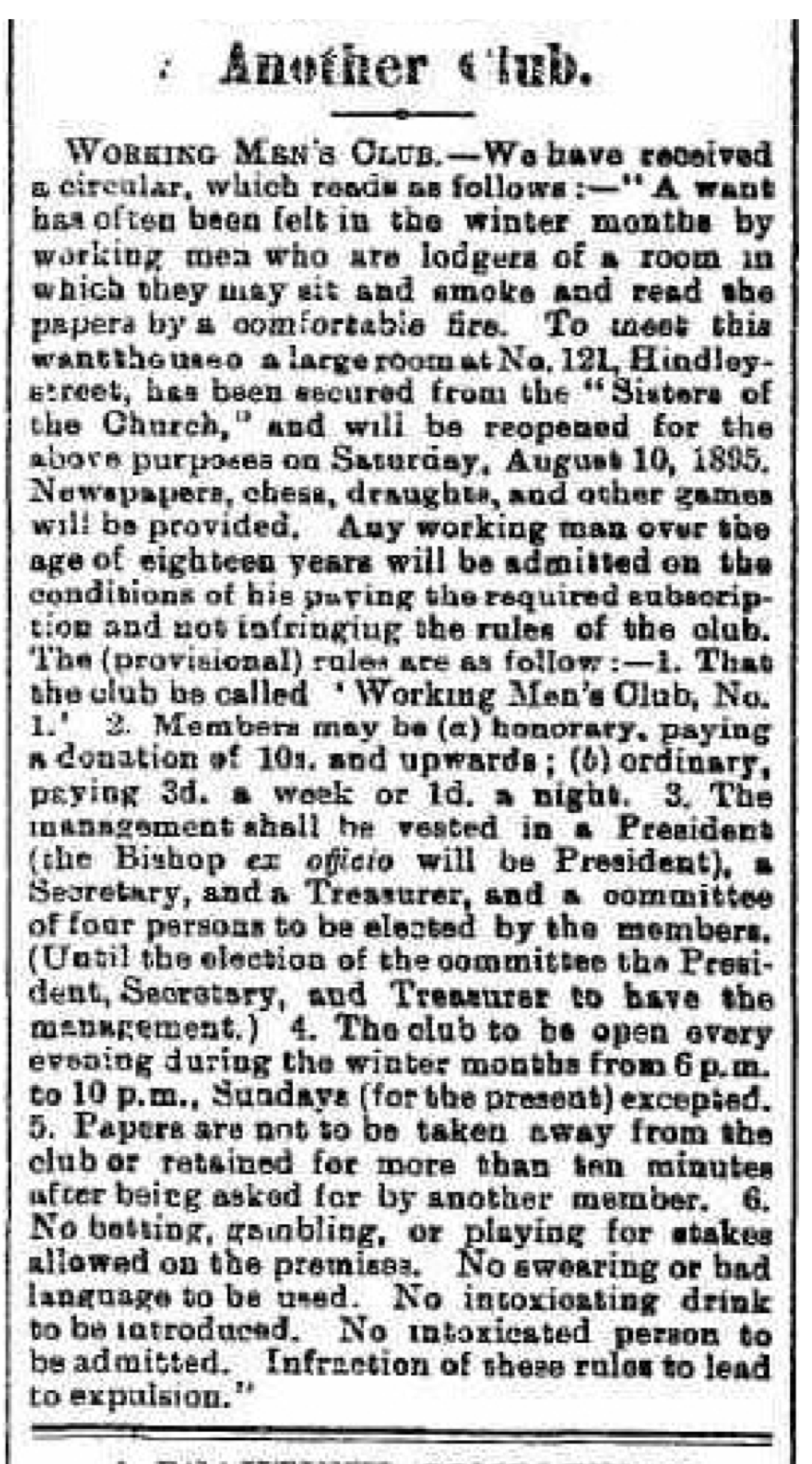

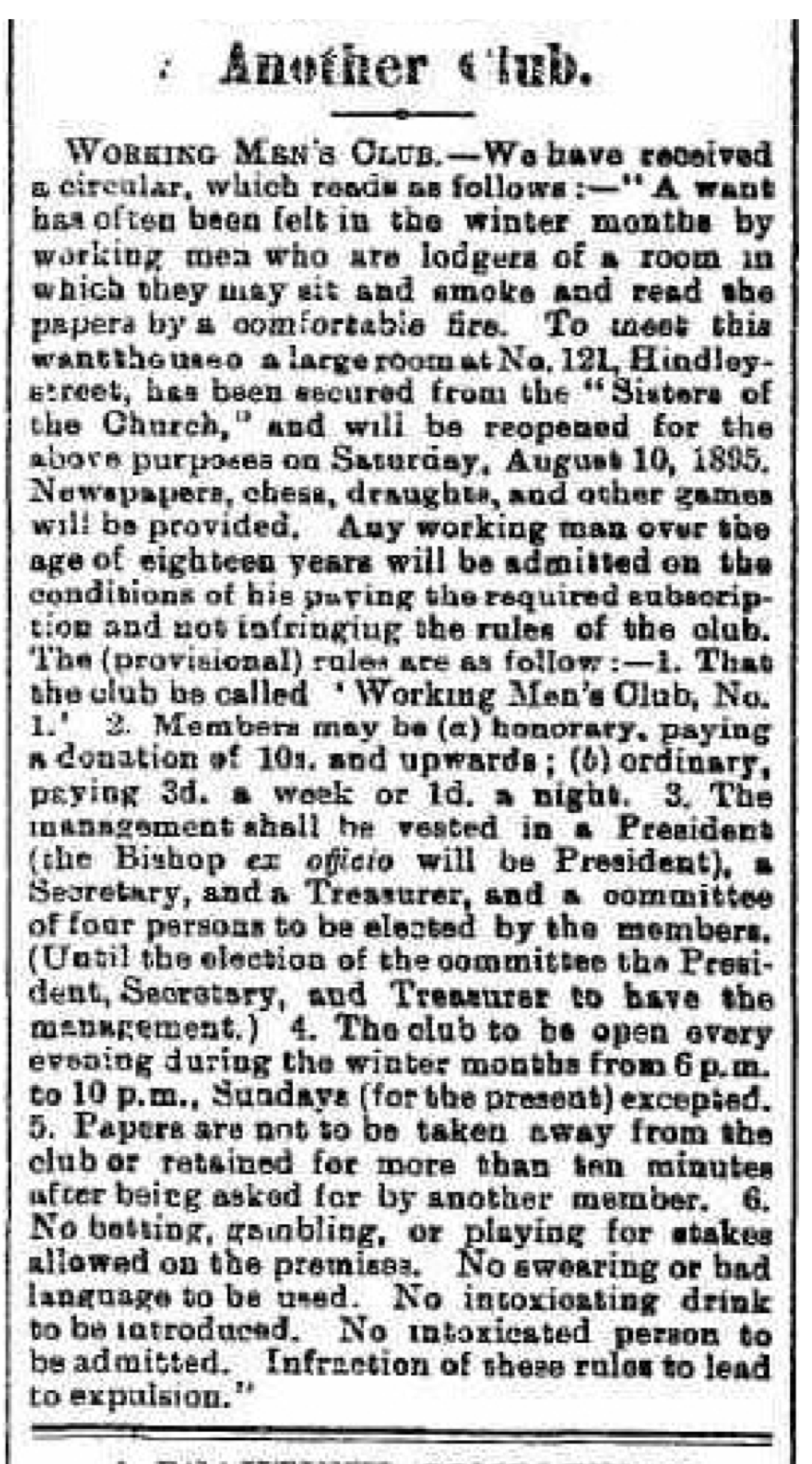

The Adelaide Working Men's Clubs

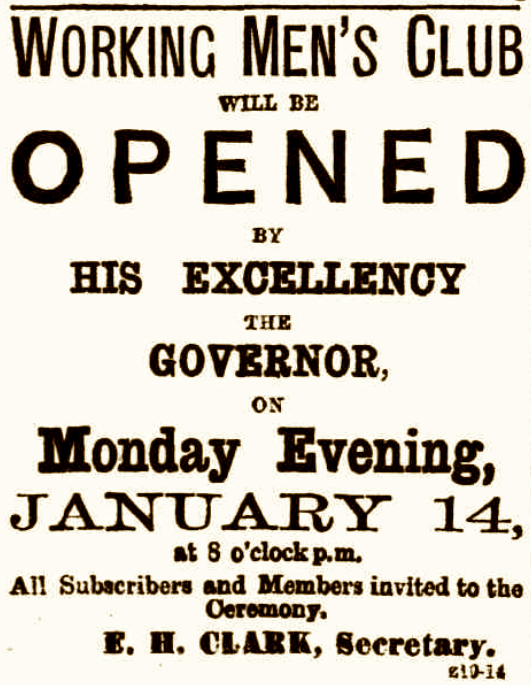

Initially proposed in June 1880 and supported by some of Adelaide's most illustrious (including at least three directors of brewing companies), the first Adelaide Working Men's Club did not come to fruition until January 1884. By March 1885 the club was insolvent probably because of mismanagement and closed soon after. A second iteration opened in May 1885 and yet a third, the Adelaide "Working Men's Club No.1" in August 1895; neither of these seem to have lasted more than a month or two [10].

Advertisement for the opening of the first Adelaide Working Men's Club, January 1884.

[Express & Telegraph, 12 January 1884, p.4] According to The Advertiser, 11 December 1883, the club premises...consist of the two upper floors of Messrs. D. &. W. Murray's establishment, No. 6, Rundle Street. The lower of the two floors...is to be divided into a refreshment and reading-room, a saloon, ladies' coffee and committee rooms. The upper floor...is to be divided into a lecture ball and billiard saloon and several ante-rooms. A lavatory, bathroom, and other conveniences are provided. Tbe place is to be fitted up and

furnished in a superior style throughout, and when finished will make an exceedingly comfortable and commodious club-house. The club is to be opened early in January, 1884.

|

|

Opening of the (third) Adelaide "Working Men's Club No.1", 1895

[Evening Journal, 7 August 1895, p.3; Click image to enlarge]

|

A major reason for the failure of WMCs was most likely financial. Although the organisers typically claimed that membership fees and/or monthly subscriptions were set deliberately low to attract members, it seems that club fees might have amounted to as much as one and a half times the daily tradesman's wage - perhaps not excessive, except in times of economic recession such as the late 1880s and 1890s. Another major factor was that, at the same time as WMCs were being established, South Australians could avail themselves of an increasing range of distractions on which to spend their increasing leisure time. The more temperate workers and their families had free access through their churches or religious societies to many of the uplifting recreations that the WMCs aimed to provide. Lodges performed similar functions. However I suspect that working men and women were more inclined to join sporting or similar clubs, to attend football matches or horse races or to patronise the popular dancing halls, theatres and music halls or, after the introduction of cheap transport, to enjoy an afternoon's excursion with their families to the beach or nearby recreational parks [13]. Or, of course, to enjoy the simple pleasures of the public house, unfettered by club rules and officials and moral crusaders.

Interior of the Norwood Club, 1911; the Norwood WMC changed its name to the "Norwood Club" in 1886.

[SLSA PRG-280-1-3-77]

|

|

Advertisement for Boddington's Theatre and Concert Hall, 1868

Boddington's was probably the first music hall built in a pub in Adelaide.

[Express & Telegraph, 20 February 1868, p.1]

|

Most South Australian WMCs were founded on temperance lines. By the mid 1870s it had become apparent, however, that the prohibition on the sale of liquor at club venues and therefore a significant loss of potential revenue was a major reason for their failure. The local press repeated British newspapers' reports on 'How to Make Workmen's Clubs Successful':

|

|

The failure of many of these institutes is attributed... to well-intentioned but injudicious endeavours to interfere with the free action of members in the working of their clubs. ...Although these clubs "without the drink" may do a large amount of good,... if the great body of the working population are ever to make use of clubs instead of publichouses, and if the clubs are to solve the public houses difficulty, the members must be able to get there such refreshments as they have been accustomed to and may desire. In fact, the working men must be trusted in their club-houses as gentlemen are trusted in theirs, to use and not to abuse the refreshments that are supplied. [14].

|

As private rather than public drinking spaces, until the late 1870s clubs were not regulated by South Australian licensing legislation any more than private houses and, although the evidence for this is circumstantial and sparse - suggesting that the practice was unexceptional - at least some WMCs certainly sold liquor to their members and visitors. However, the Licensed Victuallers Amendment Bills of 1876 and 1877 triggered lively debate regarding the licensing of clubs in general, their preferential treatment compared to public houses, and their regulation, especially in regard to Sunday trading. In Parliament John Ingleby MHA introduced an amendment to extend the prohibition on Sunday trading to "any member of any club or such places where wine, beer or spirits are vended or supplied". The change was supported, not only on religious and temperance grounds, but in the interests of social equity: "if the poor man could not obtain his beer on the Sunday, the rich man living in his club should not be able to obtain it"; William Townsend MHA predicted that if the amendment was not successful, "the effect of the Bill...would be to promote the establishment of working men's clubs." [15]. Ingleby's amendment failed and, judging by the number of cases bought to court against them, the number of clubs supposedly established just to circumvent the licensing legislation did increase. Interestingly the cases seemed to have been exclusively against "working mens' clubs" or similar, not elite "Gentlemen's" clubs. Whether clubs should be able to supply liquor to their members became as much a question about social equity as temperance. As the Kadina and Wallaroo Times concluded, "the system which now obtains is class legislation of a most pernicious description" [16].

Unsuccessful attempts to prosecute the Murray Bridge Working Mens' Club from April to June 1885 [17], then the Islington Working Mens' Club in 1885 and again in 1890 [18], and more socially egalitarian associations such as the Adelaide Democratic Club in 1889 [19] pointed to the need for Parliament to legislate in relation to clubs and liquor [20]. In June 1885 the Murray Bridge Working Mens' Club appealed its conviction in what was regarded as a test case; the Mount Barker Courier argued that "very large issues are involved in this case...

|

|

If the police succeed in demonstrating the illegality of the Club all similarly constituted establishments must forthwith cease operations. If on the other hand, [the appeal] is upheld it is more than probable that there will be a rapid increase and multiplication of Working Men's Clubs and kindred organisations in Adelaide and the country districts... It will then be incumbent upon the Government to make such alterations in the Licensed Victuallers Act as shall clearly define the position of Clubs with regard to the sale of liquor and which will protect the legalised vendor of beer, wine and spirits. [21].

|

The Licensed Victuallers Amendment Act of 1891 legislated finally for the licensing and regulation of all clubs. Well, almost all clubs: the Parliamentary refreshment rooms and military "canteens" and officers' messes were excluded. And almost finally: of the 17 clubs which applied for club licenses in March 1892, the Adelaide Licensing Bench refused 11; and as one letter to the editor of the Evening Journal noted, the Act meant that "the Adelaide Club and a few others used by wealthy people are allowed in existence and every club used by ordinary citizens for their convenience is ordered to be closed" [22]. Two of the unsuccessful clubs - the Allgemeiner Deutscher Club and the Democratic Club - referred the decision to the Supreme Court on a technicality which effectively deferred the implementation of the legislation until the revised Licensed Victuallers Amendment Act of 1896 [23].

Of course not all clubs that applied for licenses were WMCs, genuine or otherwise. From 1892 to 1897, with only two minor exceptions, the successful clubs were either upper- and/or middle-class "Gentlemen's" clubs as exemplified by the Adelaide Club or professional organisations such as the South Australian Commercial Travellers' Association or the journalists' Savage Club [24]. The Licensing Bench argued that only these clubs permanently occupied club premises, had a stable membership of at least the prescribed number, provided accommodation for members, employed staff and could produce the administrivia (management committee, rules etc) as required by the Act. However, as the Advertiser editorialised in March 1892, "if there is anything worse than class legislation, it is class administration...

|

|

If clubs are to be chartered at all, there ought to be no distinction between classes. The club whose members pay a subscription running annually into ten, twenty or it may be fifty guineas, rejoice in the possession of luxurious sleeping and dining accommodation, play on the best billiard tables that Alcock can manufacture, risk their piles of sovereigns on the chances of the cards and the dice, and gratify patrician palates with the vintages of Moet and Chandon or of Pommery, has no better right to legal recognition than a club of working men which perchance offers no greater attractions than a homely brew of colonial beer, a game on a bagatelle table, a friendly turn at cribbage or euchre with drinks on the game, or a still milder dissipation of dominoes or draughts.. [25].

|

The 1896 Act did little more than the 1891 Act to define what constituted a bona fide club but it did limit the Licensing Bench's discretionary powers in awarding and removing club licenses. Clubs were henceforth treated more or less in the same way as public houses - and, incidentally, as railway refreshment rooms, wine bars and ships and, like all licensed premises, they were subject to regular inspection and 'local option' - and this effectively removed the most blatant and overt 'class' bias from the licensing legislation if not completely from its administration. Although the number of applications for club licenses remained at about 17 per year, +/- 2, from 1892 to 1914, the proportion of club licenses granted rose from 32% in 1892 to 90% in 1897 to 100% thereafter [26].

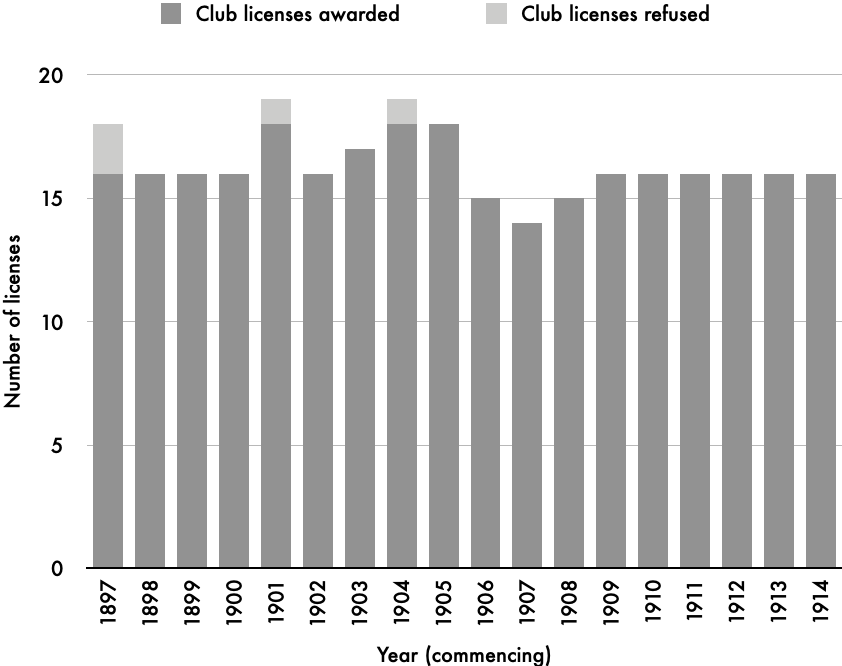

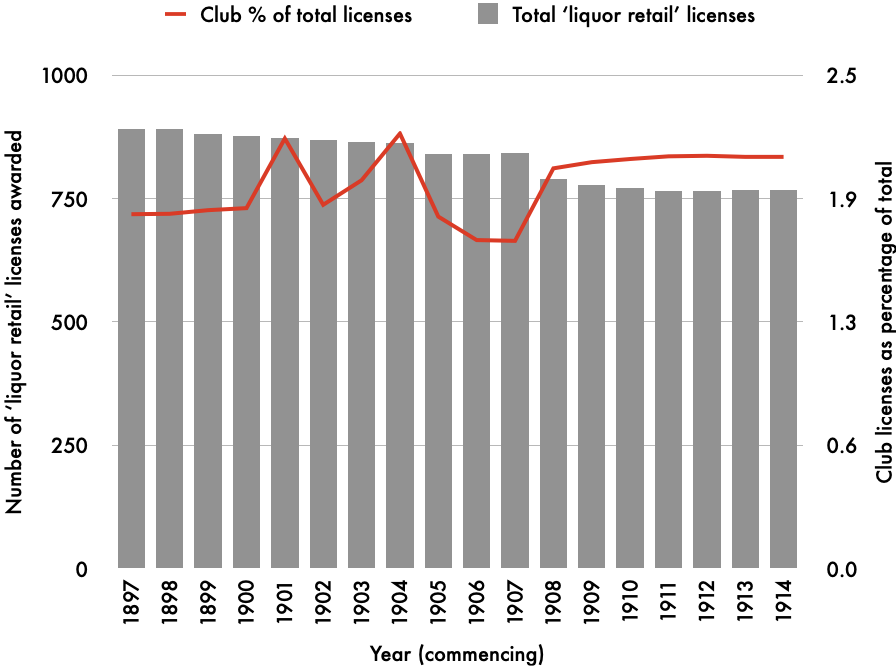

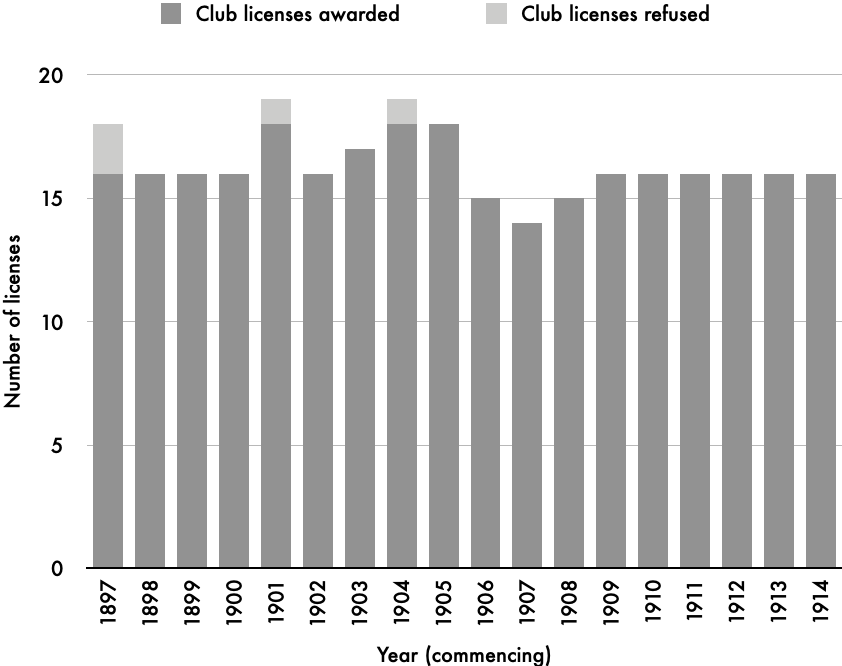

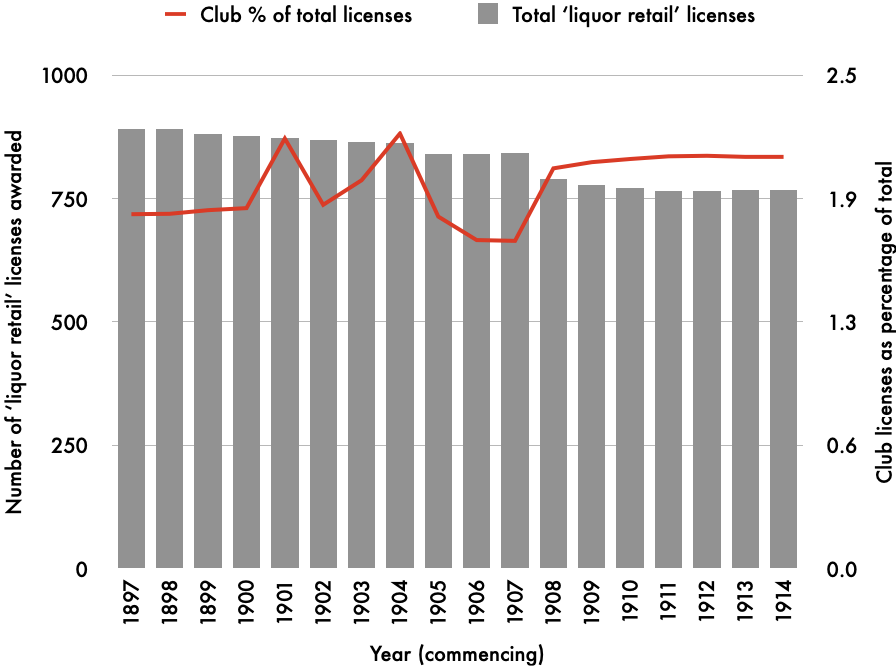

To a great extent the issue of club licensing was little more than a storm in a beer glass, a 'pony' at that [27]. The number of licensed clubs was small; as Table 1 shows, from 1897 to 1914, the number of club licenses awarded ranged from 16 to 19 per year with a median of 16. Similarly, as shown in Table 2, over the same period club licenses represented an average of only 1.9% of total 'retail' liquor licensed premises - that is, non-private places where, legally and regularly, liquor could be purchased and consumed. The low number and proportion of club licenses suggests that, despite the concerns of the Licensed Victuallers' Association, South Australian clubs did not threaten pubs and were not established as simply places to have a drink, to relax or to be entertained, as Pete Brown found in 'The North' of England [28].

Table 1: Number of club licenses awarded and refused, 1897-1914

[South Australian Government Gazette, 1897-1915]

|

|

|

Table 2: Club licenses as a percentage of the total number of 'liquor retail' licenses awarded, 1897-1914

[South Australia, Statistical Register, 1897-1915]

|

|

However, club licensing did have important and enduring symbolic value, especially for members of the "intellectual class" and aspirational workers since it placed him - but not yet her - at the same level socially as the patrons of the elitist "North Terrace Gentlemen's" clubs, most notably of the Adelaide Club [29].

Few of the clubs that applied for liquor licenses in these years were even nominally Working Men's Clubs let alone genuine Solly-esque WMCs. Of the thirty separate clubs that sought licenses from 1892 to 1897, 4 or 13% (Blinman WMC, Federal or Eastwood WMC, Norwood WMC, Sedan WMC) were called "working Men's Clubs" and by 1897 all of these had dropped even the name. On the other hand, the majority of licensed clubs appear to have been upper- or middle- or, at best, aspirational working-class. At least 6 (20%) were exclusive gentlemen's residential clubs, 3 (10%) served middle-class professionals such as stock brokers and commercial travellers and as many as 6 (20%) catered mostly for local businessmen. Even the 5 (17%) sporting clubs represented upper- and middle-class pastimes such as lawn bowls, yachting, cycling, and horse-racing. Licensed clubs as well as teetotal WMCs, it seems, had nothing to offer South Australian working men and their families that wasn't already provided by public houses.

After the First World War, South Australian WMCs seemed to have followed a path similar to that Pete Brown found in 'The South' of England. After auspicious beginnings, the number of Solly-esque WMCs dwindled rapidly; the few so-called 'Working Mens' Clubs' that opened from 1914 until the 1950s seem to have been predominantly 'social' clubs. However, without access to their constitutions and rules, office-holders and lists of members, it is impossible to identify what were Working Men's Clubs amongst the many clubs and associations - sporting, cultural, musical, or educational - that workers, their partners and families joined. However, as Pete Brown also found in 'The South', several Working Men's Clubs reflected growing working class militancy from the 1890s and were directly involved in trade unions or left-wing politics [30].

The last, surviving Working Man's Club in South Australia is, ironically, the British Working Men's Club, founded in 1958 by recent immigrants, presumably to preserve something of British culture in South Australia and modelled on the clubs Pete Brown found in 'The North' of England... which more or less brings us full circle.

Notes

|

1

|

On WMCs in Britain, see Pete Brown, Clubland: How the Working Men's Club Shaped Britain, Harper Collins 2022; Ruth Cherrington, Not Just Beer and Bingo! A Social History of Working Men's Clubs (2012); Ruth Cherrington, "The development of working men's clubs: a case study of implicit cultural policy", International Journal of Cultural Policy, vol.15, no.5, 2009, pp.187-199; Ruth Cherrington, Club Historians website (UK), visited 31 August 2022.

Without an organisation comparable to the British Club and Institute Union, formal affiliation to which defined what was and wasn't a WMC, it is difficult to identify genuine South Australian WMCs. Many, as noted below, were only nominally Working Men's Clubs; at the other end of the spectrum, yet others, such as the [Adelaide] Democratic Club, did not call themselves "Working Mens' Clubs" but shared many of the objectives of WMCs and encouraged working class participation. Between were organisations such as Mechanic Institutes, cultural clubs and even lodges. Here I have characterised Solly-esque Working Mens' Clubs as "WMC"s and those otherwise as "Working Men's Club".

|

|

2

|

Pete Brown, Clubland: How the Working Men's Club shaped Britain, pp. 44-45

A contemporary Australian report in the Sydney Morning Herald and subsequently republished in several major newspapers in other colonies, including South Australia, described the early British WMCs:

|

|

...the object of working-men's [clubs] was...to provide rooms wherein [working-men] might by the payment of a small monthly subscription become their own landlords, supply themselves with good fires and light, enjoy better conversation, bigger companies and better fellowship, at a less cost than "mine host's" nominally cheap entertainment. From these clubs intoxicating drinks were excluded, but tea, coffee, &tc was provided to members at a low charge. There was a central committee of ladies and gentlemen, and each club room was conducted by an executive committee of working men, elected by themselves every six months. Books, newspapers, and games were admitted, and there were places where members could quietly write letters to their friends. Every member was expected to protect the property of the club, and to see that its rules against gambling, bad language, &tc were strictly enforced. The club, admission to which was a penny week, was kept open from six to a quarter past ten every night, and on Saturday till eleven. It was not intended to make the members teetotallers...[and] it was considered essential, in order to reach the lowest and most ignorant classes, to permit games and smoking... Such games as chess, draughts, dominoes, bagatelle... were freely admitted… Cards and dice were prohibited... To increase their domestic pleasures together, there were weekly readings, recitations and singing, to which members were specially invited to bring their wives and families, free, that they might unitedly enjoy an evening of recreation and instruction. There were two benefit societies for members... They had two elocution classes... they had coal clubs, shoe clubs, penny banks, clothing clubs...." Sydney Morning Herald, 2 October 1863, p.5

|

|

|

3

|

Stephan Petrow, "Leisure for the toilers: the Hobart Working Mens' Club, 1864-1887", Tasmanian Historical Research Association: Papers and Proceedings, Vol 49 (2), pp.71-87, June 2002

The Hobart WMC survives as the Hobart Workers Club.

|

|

4

|

Adelaide Express 19 December 1863 p.2 and 23 December 1863 p.2; South Australian Advertiser 21 January 1864 p.2

|

|

5

|

South Australian Register 10 June 1865, p.2 and 14 July 1865, p.2

|

|

6

|

Examples of South Australian Working Mens' Clubs include: the Mitcham Working Mens' Club (established in June 1872) [7], the Gawler Workers' Association (by October 1876) [8], the Port Adelaide Working Mens' Association (about 1872) and the Port Adelaide Working Men's Club (June 1880) [9], the Adelaide Working Men's Club (January 1884 and, after insolvency, again in May 1885 and again in August 1895) [10], the Norwood Working Mens' Club (December 1884) [11] and the Murray Bridge Working Mens' Club (by 1885) [12].

|

|

7

|

Evening Journal, 5 June 1872 p.3; Adelaide Observer, 17 August 1872 p.7;

|

|

8

|

Evening Journal, 9 October 1876 p.3 |

|

9

|

Despite sharing some features of WMCs, the Port Adelaide Working Men's Association was established primarily as an early trade union for waterside workers. The Port Adelaide Working Men's Club was established by local employers and merchants to oppose the activity of the Association; it incorporated a labour hire office; it possibly transformed into the Port Adelaide Working Men's Rowing Club by about 1890.

On the Port Adelaide Working Men's Association: Evening Journal, 19 August 1872, p.2; South Australian Register, 7 September 1872, p.6; South Australian Register, 21 September 1872, p.2; South Australian Advertiser, 23 September 1872, p.3. On the Port Adelaide Working Men's Club: Evening Journal, 22 June 1880 p.2; Evening Journal, 23 November 1882 p.1

|

|

10

|

Evening Journal, 23 June 1880 p.3;

Evening Journal, 23 October 1883 p.3;

South Australian Register, 11 December 1883 p.4;

Evening Journal, 15 January 1884 p.3;

Evening Journal, 29 November 1884 p.6;

South Australian Register, 17 March 1885 p.6;

Evening Journal, 7 May 1885 p.4;

Evening Journal, 7 August 1895 p.3;

Express and Telegraph, 12 August 1895 p.4

|

|

11

|

Daniel Manning and Deborah McKenzie, The first 100 years, 1884-1984: a history of the Norwood Club Inc 1984; Norwood Club ephemera collection at the State Library of South Australia.

Evening Journal, 29 November 1884 p.6; Evening Journal, 3 December 1884 p.3

|

|

12

|

South Australian Weekly Chronicle, 25 April 1885 p.22; South Australian Register, 29 April 1885 p.4; Express and Telegraph, 4 June 1885 p.2 |

|

13

|

On alternative popular pastimes: the first genuinely and semi-permanent 'variety' music hall in South Australia seems to have been Thomas Boddington's theatre, built as part of the Shamrock Hotel on Currie Street at Light Square in 1868. Although the evolving 'Australian' football was hardly a working-class sport at this time, the Adelaide Football Club was founded in 1860 at the Globe Hotel in Rundle Street. Clubs for coursing (the precursor to greyhound racing), pigeon racing, quoits and bowling were established in 1875, 1885, by 1872 and in about 1877 respectively. Rail services to beaches at Glenelg and Semaphore were opened in 1873 and 1878 respectively and to Belair Recreational Park and the Government Farm in 1883.

|

|

14

|

Border Watch [Mount Gambier], 18 September 1872, p.3

|

|

15

|

Evening Journal, 9 October 1876, p.3; South Australian Chronicle and Weekly Mail, 14 October 1876, p.7

|

|

16

|

Kadina and Wallaroo Times 3 April 1889 p.2 |

|

17

|

Mount Barker Courier and Onkaparinga and Gumeracha Advertiser 5 June 1885, p.2; Adelaide Observer 6 June 1885, p.38; Evening Journal 18 November 1886, p.3 |

|

18

|

Evening Journal 18 November 1886, p.3; Evening Journal 14 February 1890, p.2 |

|

19

|

Advertiser 12 October 1889, p.6 |

|

20

|

According to the Chief Secretary of the House of Assembly, from June 1889 to June 1891 "there were 18 clubs which supplied intoxicating liquor to their members; 35 charges had been laid against these clubs for illegally selling liquor; 11 convictions had been obtained" Advertiser 26 August 1891, p.4.

|

|

21

|

Mount Barker Courier and Onkaparinga and Gumeracha Advertiser, 5 June 1885, p.3

|

|

22

|

Express and Telegraph 10 March 1892, p.3; Evening Journal 12 March 1892, p.5

|

|

23

|

Express and Telegraph 29 December 1892. p.4 |

|

24

|

South Australian Register 10 March 1892, p.7

|

|

25

|

Advertiser, 29 March 1892, p.4

|

|

26

|

Here and below, the data on club licenses is taken from the South Australian Government Gazette, 1892 - 1915; For the record, a working (ie rough, occasionally inconsistent and possibly inaccurate) version of the tabulated data is posted here.

|

|

27

|

At only 140ml (half the capacity of a South Australian 'schooner'), a 'pony' is the smallest glass in which beer is sold, but rarely, in South Australian pubs.

|

|

29

|

Since its inception in 1863 the Adelaide Club has, perhaps at times unjustifiably, epitomised status, privilege, influence and conservatism. Its membership has included many of South Australia's commercial, political, religious and judicial leaders. One of its founding members, for example, was Samuel Tomkinson, banker, politician, magistrate, member and President of the Licensing Bench etc.

Because the club was "established before the first day of January one thousand nine hundred [and was] used bona fide and mainly for residential purposes" and that "liquor is not drunk in any bar-room" on club premises, in August 1910 the Adelaide Club was exempted from the provisions of the Licensing Act of 1908 [South Autralian Government Gazette, 18 August 1910, p.1]. The exemption applied to the Licensing Act Further Amendment Act of October 1915 which prohibited the sale and consumption of liquor on licensed presmises after six o'clock in the evening. When the law came into effect on 27 March 1916 "a large crowd began to concentrate at the intersection of King William and Grenfell Streets, in front of the Imperial Hotel". E J Cummins, representing the Licensed Victuallers' Association, addressed the crowd - "Tonight the public houses close at 6 o'clock. You and I are prevented from having a drink. The landlords offer the public good drink and good accommodation. Six o'clock closing is going to push the drink into the homes of people. If you were Britishers you would not stand by and do nothing while the Adelaide Club is allowed to remain open" - and then led about 1000 men down King William Street to the Adelaide Club on North Terrace; after much hooting and jeering" and more speeches, the crowd eventually dispersed [Express and Telegraph, 28 March 1916, p.3].

Significantly, popular resentment over six o'clock closing was directed at the Adelaide Club and privilege rather than at the Temperance Alliance and its supporters who were assembling at the same time at The Exhibition Hall a little further east on North Terrace.

|

|

30

|

Pete Brown, Clubland: How the Working Men's Club Shaped Britain, ff.107

Victor Cromer traces the "birth of the Political Labour Party" to a meeting of Trades and Labor Societies and Working Men's Clubs at the Selbourne Hotel on 7 January 1890 (Daily Herald, 2 September 1922, p.3. Several founders of the United Labor Party such as George Buttery (Weekly Herald 27 November 1896, p.1; Herald 16 November 1907, p.3) and William Archibald (Herald 19 October 1901, p.1) had been involved in the Working Men's Club Movement in Britain. The Lefevre Peninsula Working Men's Club, founded in November 1897 at the Glanville Hotel, was "practically a branch of the United Labor Party" (Weekly Herald 19 November 1897, p.3), similarly, the West Torren's Working Men's Association, established in October 1896 at the Lady Daly (Weekly Herald 16 October 1896, p.5). In August 1929 the Wharf Workers' Union established "a cooperative canteen and club" for its members (Advertiser 5 August 1929, p.6) and, in April 1949, the Waterside Workers' Federation planned a working men's club at Port Adelaide (Mail 23 April 1949, p.36)

|

• • •

Posted 27 September 2022 Original content © Craig Hill 2022

| |